Charity Abroad, Community at Home

How Indian Education Nonprofits Foster Engagement Among Volunteers in the United States

On October 23, 2021, three Indian Americans participated in the final round of SelectChef, a cooking competition hosted in New York City and judged by Vikas Khanna, Michelin Star Indian chef and host of MasterChef India. As described in a news brief, the competition sought to "bring chefs and foodies back to their roots" as they embraced family recipes from their Indian heritage.

At first glance, this event seems like one hosted by a local Indian culinary association, similar to a reality TV competition like MasterChef. However, SelectChef's goals were not limited to culinary appreciation, as the event was in fact a fundraiser hosted by a 501(c)3 nonprofit named Vibha. Based in New Jersey, Vibha was founded in 1996 to promote the education of millions of underprivileged children in India by encouraging donations and hosting fundraising events in the United States ("Vibha Atlanta" 2018).

As a first-generation Indian American and youth volunteer for Vibha myself during high school, I had experienced a taste of how Vibha cultivates community for Indian Americans through its culture-based fundraisers, similar to SelectChef. Motivated to understand this trend at a deeper level, I wondered how Vibha, as well as other popular Indian education nonprofits, foster engagement among Indian Americans.

Background

Indian Education Nonprofits and the Indian Diaspora

Education in India is a stark example of an issue demanding the attention of nonprofits. According to UNICEF's studies, 50% of Indian adolescents do not complete secondary education, and the National Sample Survey Office finds that 32 million Indian children have never been to any school (Modi 2020). However, the government has been largely passive and ineffective in addressing this issue. Despite national education policies since 1968 that have set a benchmark of spending 6% of GDP on education, India spends only 3% (Swamy 2021). A number of nonprofit organizations have emerged in an attempt to compensate for this lack of government involvement. Out of 42 designated subcategories of nonprofits in India, education is the most concentrated, including 8.02% of all nonprofits registered with NGO DARPAN, a platform developed by India's National Informatics Center (More 2021).

Especially since the 1990s, Indian education nonprofits have started gaining footing abroad, largely due to the growing population of people of Indian origin in other countries. In fact, as of 2019, Indian Americans, consisting of Indian immigrants as well as their descendants, are the second-largest immigrant group in the U.S., with 4.2 million people of Indian origin residing (Badrinathan 2021). In line with this trend, some nonprofits that were founded in India itself have expanded to form chapters in the Americas, while others have been founded in the United States by individuals of Indian descent.

Many scholars have commended the importance of cultural organizations for the Indian diaspora and the emphasis placed on community and benevolence in Indian values. Other scholars have pointed to issues of apprehension and indifference precluding Indian American involvement with Indian nonprofits. This discrepancy has compelled me to study how real-world examples of Indian education nonprofits are engaging with the Indian American population. Previous scholarly discussion about Indian nonprofits has centered around their use of donations and service abroad programs to further their mission. However, studies have not considered whether nonprofits specifically appeal to Indian American identities, or how they promote community and culture among Indian American volunteers and participants themselves. Therefore, my aim has been to understand the strategies that Indian education nonprofits use to foster engagement among Indian Americans in the United States.

I analyze the websites and social media platforms of three particularly successful organizations: Vibha, Asha for Education, and Pratham USA. The former two were founded in the United States, while the third is the United States chapter of an India-based nonprofit. I argue that these nonprofits appeal to Indian Americans' affection for their Indian heritage, even when simply requesting donations, and foster a sense of community through local fundraising events centered around Indian values and culture. I discuss the manifestation of these strategies through four ways. First, I identify their use of references to well-known Indian figures and symbols to encourage Indian Americans to donate. Second, I discuss fundraising events inspired by popular Indian culture and hobbies. Then, I characterize the nonprofits' strategic balance between establishing secularity in mission and use of funds, contextualized by rising concerns about the Hindutva movement, and embracing Hinduism's importance for the diaspora when hosting religious celebrations. Lastly, I highlight how nonprofits cater to Indian immigrants' aspirations for their children through opportunities for youth. Ultimately, my findings demonstrate that nonprofits are a unique avenue for cultivating cultural appreciation among Indian immigrants and their children, and that emphasizing community-building bolsters volunteerism among the diaspora.

Scholarly Perspectives on Indian Americans and Nonprofits

Before delving into the rhetoric behind fostering volunteer engagement, it is essential to understand the ways in which Indian American individuals and communities in the United States connect with their Indian heritage more broadly. In an interview-based analysis of the Indian American community in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, Caroline B. Brettel found that immigrants created and relied on religious, regional, and ethnic organizations, such as the Gujarati Associations in the US and the DFW Hindu Temple, in order to build social networks and find a sense of community (Brettel 2005, 859). The study also analyzed the immigrant parents' aspirations for their US-born children. One parent expressed his desire to "expose our children to their culture so that they will not miss any of it and then blame us later for not teaching it" (Brettel 2005, 861). As a result, some regional clubs have begun to host language and dance classes in order to halt "radical Americanization," hinting at the risk of Indian American children becoming disconnected with their Indian culture. While this study does not explicitly analyze volunteering, it demonstrates that the fear of missing out from Indian culture while living abroad, coupled with Indian immigrants' sense of obligation to pass on their culture to the next generation, has proven to be a motivating factor in amplifying involvement with local organizations.

Scholars have also studied trends of volunteering among Indian immigrants. In a qualitative study of Asian immigrants in the United Kingdom in the 1990s, Wells and Raheja claim that the strong philanthropic tradition, communal ties, and work ethic in Asian cultures position immigrants to be particularly effective as volunteers (Wells and Raheja, 1997). On the other hand, as Counts and Venkatachalam highlight in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, this potential is not reflected in reality, as Indian Americans currently give at one-third the rate of the overall U.S. population. The pair believes that this trend is due to "growing disconnect" between children of Indian immigrants and their Indian heritage, as well as doubts about the "honesty and efficiency" of Indian nonprofits, which are exacerbated by repeated pleas to donate and attend promotional "gala dinners" (Counts and Venkatachalam, 2019). Given the contrast between these observations, it is worthy to analyze whether Indian nonprofits have started to capitalize on factors such as tradition and work ethic when recruiting Indian immigrants, as well as whether there are strategies more effective than seeking donations and advertising gala dinners.

Specific research regarding Indian nonprofits' techniques has been limited but has largely focused on donations and service abroad programs. In her analysis of Indian nonprofits' websites in 2016, Noorie Baig argued that such websites "commodify hope" and "exploit smiles for marketing," ultimately portraying Indian children as otherized and needing the benevolence of "privileged'' and "generous'' Indian Americans (Baig 2016, 18). Other scholars have highlighted the role of service abroad programs, which enable students to physically travel to India and volunteer with nonprofits. Notably, Chow and Cho of the International Institute for Education highlight India as a country with strong potential for "service learning" opportunities due to its "large number of nonprofit, development and service organizations, as well as multinationals and corporations with U.S. partners" (Chow and Cho, 2011). These studies indicate that Indian organizations are aware of Americans' financial ability to support nonprofits and are actively seeking to garner their interest.

However, they do not explore marketing specifically targeted to Indian Americans, which is necessary to study given that Indian Americans seem to form a backbone of these nonprofits' successes. In fact, all of the volunteers pictured in Vibha's 2019 Annual Report are of Indian descent (Vibha Inc 2019). Additionally, these studies have not considered a third aspect that is directly relevant to volunteering among Indian Americans - fundraising events. In the case of nonprofit Vibha, fundraising events are organized by its global chapters multiple times a year, and people can choose to engage either through buying tickets and participating or volunteering to organize the event. More importantly, fundraising events were the source of 45.5% of the nonprofit's revenue in 2019, indicating the crucial role these events play in a nonprofit's success.

Ultimately, analyzing appeals specifically to Indian Americans, as well as fundraisers and the associated engagement that takes place in the United States, provides key insight into the relationship between nonprofits and the Indian diaspora.

Analysis of Indian Education Nonprofits' Websites and Social Media Pages

The Three Nonprofits: Vibha, Asha for Education, Pratham USA

Each of the three nonprofits I study are worthy of analysis due to their distinguished degrees of success in the United States. With a base of 2200 volunteers and 1500 volunteers respectively, US-based Vibha and Asha for Education have become household names among the Indian American community due to their popular fundraising events, which have led to over $18 million worth of educational projects, and youth chapters. Despite its parent organization being India-based, even Pratham USA has been ranked among the top 2% of United States charities due to its emphasis on partnerships and collaborations with communities. These nonprofits' active online presence, numerous chapters across the states, and frequent fundraising events provide ground for comprehensive investigation of their various strategies.

Overall Branding

The three nonprofits' overall approach to branding, as best seen through their names and logos, provides important context for their strategies to foster engagement. Vibha, Asha for Education, and Pratham USA all have Sanskrit names. "Vibha" means "shining" and "bright," giving a glimpse into the organization's vision to provide a "brighter future" to underprivileged children (Vibha Homepage 2021). Similarly, "Asha" translates to "hope," and "Pratham" means "first," aligning with its emphasis on innovation, advocacy, and inspiring change in the sphere of non-governmental education organizations (Pratham USA Homepage 2022). The organizations' logos similarly reflect their dedication towards children and education, with all three including either a child or a smiling face. More notably, Asha for Education's logo features two girls with classic Indian hairstyles, such as two braids and a tight middle parting (Asha for Education 2019). Therefore, not only do these organizations spotlight ideas of positivity as Noorie Baig had argued, but they do so with a distinct Indian touch, suggesting that these nonprofits also seek to draw the attention of Indian Americans specifically.

References to Well-Known Indian Symbols

The nonprofits' Indian touch also extends to more substantive aspects of their websites and social media pages in the form of references to well-known Indian figures and landmarks. On August 15, 2020, a North American chapter of Asha for Education took advantage of the occasion of Indian Independence Day to reinforce its mission and request donations. The chapter posted on Facebook, "Be it Mahatma Gandhi or Bhagat Singh, history is proof that education played a crucial role in the freedom struggle of India" (Asha for Education 2020). By citing well-known Indian activists, the post invokes a sense of patriotism and moral responsibility to continue their legacy and support education. The post proceeds to encourage readers to "honor India's vision, rich culture, and tradition," highlighting that their donation not only benefits children but also India as a country and source of identity. The post's final quote, “Padhega India, toh badhega India," which includes a translation, "When India studies, it progresses," builds onto this sentiment while also appealing to Indian Americans less familiar with the Hindi language. Thus, even when simply seeking donations, nonprofits specifically target Indian Americans' sentiments rooted in their Indian identity.

The nonprofits also use references to Indian landmarks to foster relatability with younger volunteers. Asha for Education's Arizona youth chapter, which is run by volunteers ages 5 through 18, includes a stock image of the Taj Mahal on its donation page (Asha for Education: Arizona Youth Chapter 2022). Although the Taj Mahal is not intrinsically related to volunteering or children's education, it serves as an easily recognizable symbol of India, even for those not intimately knowledgeable about Indian culture. As a result, potential volunteers or participants visiting the page, many of whom would be young Indian Americans, can associate Asha with a familiar image and likely feel more comfortable supporting its initiatives.

Fundraising Events Centered Around Hobbies and Culture

Fostering engagement among Indian Americans is not limited to surface-level branding and references but also manifests in the nonprofits' fundraising events, which largely center around Indian culture and hobbies. A prominent example is a group of flyers and videos on Vibha's website, which advertise the "FutureTech Vibha Champions Cricket Cup" hosted in Georgia and New York (Vibha Atlanta 2019). The advertisement encourages readers to "combine your passion for cricket with a desire to help these children in need" by helping organize or participating in the fundraising event. Similarly, the video features Mithali Raj, captain of the Indian women's cricket team and sponsor of the event, saying "Go India! Go Vibha! Pad Up!" It is important to note that cricket is the most popular sport in India, and India consistently ranks as one of the top three nations in the sport. Thus, Vibha is explicitly targeting Indian Americans, many of whom may share the hobby, rather than hosting a more generic fundraiser with appeal to other ethnic groups in the United States.

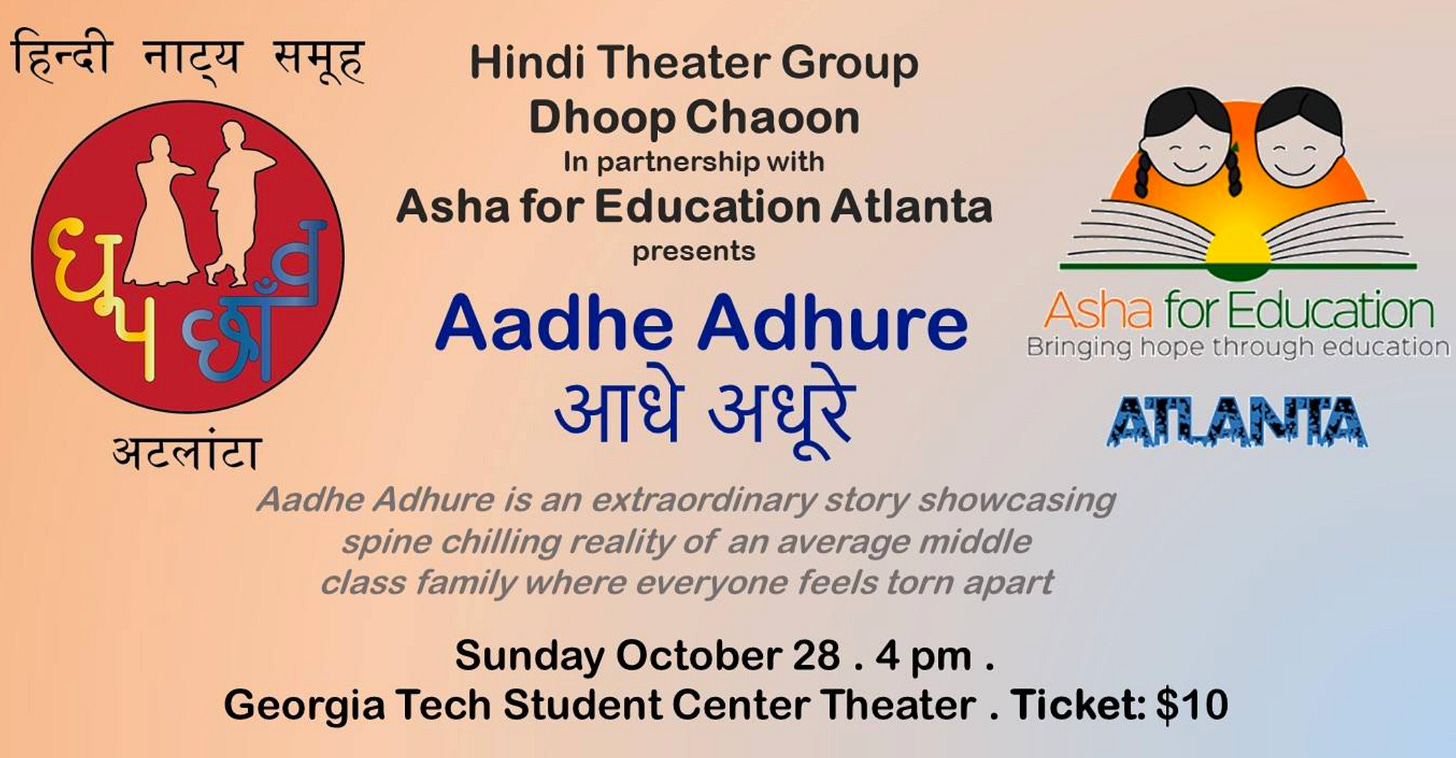

Asha for Education integrated unique aspects of Indian culture into its fundraisers specifically by partnering with other cultural, non-volunteering organizations. In 2015, Asha partnered with Dhoop Chaoon, a Hindi Theater group in Atlanta, to host a fundraising play about families in urban India, a topic relatable to many Indian American immigrants and households (Asha Atlanta 2018). By partnering with a well-known cultural group in the region, Asha is able to reach audiences more efficiently, given that such organizations have long been a popular avenue for Indian Americans to find community (Brettel 2005). Strikingly, the flyer states the name of the play as both "Aadhe Adhure" in English and "आधे अधूरे" in Hindi. Even though all possible attendees would be from the Atlanta region and thus fluent in English, the inclusion of the Hindi name is an efficient and simple way of fostering feelings of inclusion and commonality among Indian Americans. After all, language is a powerful means of "maintain[ing] and convey[ing] culture and cultural ties."

Balance Between Religious Celebrations and Secular Use of Funds

The intertwined nature of Indian culture and fundraising events is not constrained to the realm of sports and entertainment and extends into the more nuanced, sensitive area of religion.

In recent years, India has witnessed the rise of Hindutva, a right-wing nationalism movement that seeks to advocate and establish the "hegemony of Hindus and Hinduism within India" by promoting violence against non-Hindu minorities. Due to a number of controversies surrounding nonprofits that have been exposed for funding Hindutva, more Indian Americans, as well as Americans more generally, are becoming suspicious of Hindu nonprofits, as they seek to avoid "unwittingly supporting programs or causes that covertly support 'Hinduization'" (Anand 2014).

Thus, nonprofits like Asha for Education may be emphasizing their secular nature to reassure Indian Americans that they will not fund initiatives or people that are religiously intolerant. For example, Asha constantly reiterates its identity as a "secular organization" that funds "only non-sectarian and secular community initiatives" in the About section of its website (Asha for Education 2019).

Nevertheless, Asha does not restrain from hosting religious celebrations as fundraising events. The homepage of Asha for Education's Atlanta chapter's website features a large image of nearly forty people of Indian descent wearing traditional Indian attire, such as salwar kameez and kurta pajamas (Asha Atlanta 2022). A background presentation slide for the fundraising event says "Dussehra," which is a major Hindu religious festival marking a victory of god Rama. Notably, the slide includes subtext that all proceeds from the event would support victims of natural disasters in Gujarat. In doing so, Asha for Education reinforces that while the event is centered around Hinduism, the funds from the event will only be used for secular purposes.

Similarly, Pratham USA has integrated aspects of Hinduism into its fundraisers. A 2017 blog post on Pratham USA's website proudly displays the success of Triveni Dance Ensemble, a school of dance in Boston, Massachusetts, in hosting Indian classical dance performances at Boston University to fundraise for Pratham (Pratham USA 2017). The post includes elaborate descriptions of various personas Indian goddesses represented by the dancers, such as Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Parvati. The fundraiser was a significant success, raising over $4000 through two sold-out performances. Nonprofits' incorporation of religion into events as a means for increasing participation and receiving proceeds is evidently strategic, given that religion plays an important role in the lives of nearly three-fourths of Indian Americans, who have traditionally enjoyed religious and cultural community events hosted by local Hindu temples (Brettel 2005).

Both Asha and Pratham USA maintain a balance between being secular in terms of their mission and funding and taking advantage of religious celebrations to host successful fundraising events. By doing so, they are able to secure both the trust and engagement of Indian Americans, as they foster community-building while mitigating the concerns about honesty that Counts and Venkatachalam had observed.

Opportunities for Youth

Children's education and connection with their Indian heritage is known to be especially important to the Indian American community, in line with Brettel's observation that regional associations such as the Punjabi Cultural Society prevent "radical Americanization" of children through language and dance classes. Indian education nonprofits are no exception, as they provide opportunities for kids to volunteer and participate in kid-friendly events while targeting the goals that Indian immigrant parents have for their children.

Asha for Education's youth chapters encourage middle and high school students to both join as event planning volunteers and support events as participants. For example, the Silicon Valley chapter's blog spotlighted Rohini Balusu, an Indian American in 11th grade, for hosting a fundraising event for Asha called "Expressions of Art'' involving Indian art forms such as Bharatanatyam and Carnatic music (Natesan 2018). By emphasizing Rohini's other Indian pursuits as much as her leadership in Asha, Asha demonstrates that involvement with the nonprofit also bolsters children's engagement with their Indian heritage, which Indian immigrant parents are determined to preserve. Then, by praising her as a "silent hero" and "inspiration to younger kids" in the comment section, Asha provides appreciation for Rohini's past volunteer work and motivates younger kids to follow in her footsteps. The Arizona chapter, which has younger volunteers, focuses more on encouraging participants to attend fundraising events. Their promotion for their walkathon and yoga session includes kid-friendly phrases such as "awesome cause!" and "Get ready for fun games, tasty food, and many exciting activities!" to stir enthusiasm and portray their events as enjoyable for participants.

The appeal to youth is also reflected in the content of fundraising events themselves, which cater to immigrant parents' values and aspirations for their children. The Vibha Bay Area Youth Chapter's flyer for a hackathon fundraiser begins with "Are your kids interested in coding, but don't know where to start?" (Vibha Youth Chapter 2021). This rhetorical question directly catches the attention of the many Indian immigrant parents in the Silicon Valley who "credit their success in the United States to their STEM education" and hope that their children pursue similar professions, such as computer science (Saran 2015). By capitalizing on existing desires and goals of Indian immigrant parents, Vibha is able to target their fundraisers not only to youth participants, but also parents, who play an active role in encouraging their children to engage in activities.

In parallel, Pratham USA hosted a readathon in which friends and family of Indian American children donate to Pratham based on the number of books their child reads over the summer. The news article describing the event highlights that "not only kids in India are benefiting, but local kids are also enhancing their imagination" by reading books, encouraging parents to have their children join the readathon for personal benefit (Pratham USA 2019). Interestingly, the article points out that a recommended book in the readathon was Beeline, which explains Indian American students' success in spelling bees. Pratham USA is clearly cognizant of a larger trend in the Indian American community, in which parents enroll their children in spelling bees such as the South Asian Spelling Bee. By hosting fundraisers catering to parents' desire to prepare their children for such competitions, Pratham USA gains the trust of parents who recognize Pratham as an organization that not only advances its own mission but also supports their children's academic success.

The news article also recognizes the readathon's guest speaker Varsha Bajaj, a Houston-based Indian American author who "incorporates Indian cultural elements into her picture books and stories" (Nadkarni 2019). With corresponding pictures of books with Indian characters, such as Chuskit Goes to School and Goodnight, Tinku, Pratham provides an accessible avenue for Indian immigrant parents to connect their young children with their Indian heritage.

The degree to which all three nonprofits incorporate youth opportunities into their engagement strategies is very noticeable. By not limiting themselves to adult-related events when fostering engagement among Indian Americans, the nonprofits ultimately attract a wider audience across generations while also gaining the support of adults who attend these events with their children.

Conclusion

From this analysis, we see that Indian education nonprofits do not merely seek donations from the generic American population but make concerted efforts to garner the support of Indian Americans, not unlike other Indian American community organizations. Vibha, Asha for Education, and Pratham USA demonstrate intimate attunement to Indian Americans, as they appeal to Indian Americans' affection for their Indian heritage and host local community events centered around Indian culture and values. As evidenced by references to Indian history and figures, they place Indian identity at the core of their marketing rhetoric. Fundraising events extend this emphasis in a concrete manner and build community among Indian Americans, as they are centered around Indian hobbies and culture. On the religious side of culture, the nonprofits embrace Hinduism as a unique force for community-building in the form of celebratory gatherings while being careful to clarify that funds from the events are solely used for secular purposes. Looking to the younger generation of Indian Americans, the nonprofits cater to the broader context of Indian immigrants' aspirations for their children through youth volunteering chapters and kid-friendly fundraisers.

So far, these techniques have been effective as evidenced by the nonprofits' distinctions and large volunteer bases. It is important to note that much of their volunteer base currently constitutes Indian immigrants and their first-generation Indian American children. However, the proportion of second-generation Indian Americans is expected to grow in the 21st century, and the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey found that 30% of U.S.-born Indian Americans believe that being Indian is "either somewhat or very unimportant to their identity," as opposed to merely 17% of foreign-born Indian Americans (Badrinathan et. al 2020).

As a result, maintaining cultural and community-based ties among the Indian diaspora is more important than ever. With intrinsic ties to Indian heritage declining among the next generation of Indian Americans, continued research must investigate how these nonprofits adapt their strategies to earn the interest and support of those who feel just as American as they do Indian. Fortunately, the survey also points to a solution. While nonprofits' current cultural fundraisers focused on arts or dance may not be as effective, with only 36% of respondents having participated in Indian arts in the past six months, 51% of U.S.-born respondents had watched Indian TV shows and 67% had eaten Indian food in just the past month. Thus, if Indian education nonprofits take note of such shifts and continue to remain attuned to the values and traits of Indian Americans, we will be better positioned to take the slogan “Padhega India, toh badhega India" to the next level.

References

This paper was originally written for PWR 2HK: The Rhetoric of Global Citizenship, a course at Stanford University.

Anand, Priya. “Hindu Diaspora and Religious Philanthropy in the United States.” Academia.edu, May 25, 2014. https://www.academia.edu/4781413/Hindu_Diaspora_and_Religious_Philanthropy_in_the_United_States.

“Asha Atlanta.” The Atlanta chapter of Asha for Education. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://atlanta.ashanet.org/.

“Asha for Education.” Catalyzing socio-economic change through the education of underprivileged children, December 4, 2019. https://ashanet.org/.

“Asha Atlanta.” The Atlanta chapter of Asha for Education, 2018. https://atlanta.ashanet.org/events/past-events/.

Asha for Education - Canada. Facebook, August 15, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/ashaforeducationcanada/posts/be-it-mahatma-gandhi-or-bhagat-singh-history-is-proof-that-education-played-a-cr/587273908614773/.

Badrinathan, Sumitra, Devesh Kapur, Jonathan Kay, and Milan Vaishnav. “Social Realities of Indian Americans: Results from the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 9, 2021. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/09/social-realities-of-indian-americans-results-from-2020-indian-american-attitudes-survey-pub-84667.

Baig, Noorie. “(Re)Defining Transnational Identities through Diaspora Philanthropy in South Asian Indian Non-Profit Organisations.” OpenSIUC, 2016. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol15/iss1/2/.

Brettell, Caroline B. “Voluntary Organizations, Social Capital, and the Social Incorporation of Asian Indian Immigrants in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.” Anthropological Quarterly 78, no. 4 (2005): 853–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4150964.

Chow, Patricia, and Kimberly Cho. “Expanding U.S. Study Abroad to India: A Guide for Institutions.” The Power of International Education. Institute of International Education, July 2011. https://www.iie.org/Research-and-Insights/Publications/Expanding-US-Study-Abroad-to-India.

Counts, Alex, and Bala Venkatachalam. “How 11 Humanitarian Organizations Collaborated to Strengthen Indian Americans’ Giving and Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2019. https://doi.org/10.48558/6BG4-YE43

“Donate.” Asha for Education: Arizona Youth Chapter. Accessed March 12, 2022. http://ashaazkids.weebly.com/donate.html.

“News.” Pratham. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://pratham.org/.

Modi, Sushma, and Ronika Postaria. “How Covid-19 Deepens the Digital Education Divide in India.” UNICEF Global Development Commons, October 6, 2020. https://gdc.unicef.org/resource/how-covid-19-deepens-digital-education-divide-india.

More, Saakshi. “Reimagining Education Ngos in India: A Success Playbook.” GGI, December 22, 2021. https://www.councilonsustainabledevelopment.org/post/reimagining-education-ngos-in-india-a-success-playbook.

Nadkarni, Ritu. “Pratham Houston Readathon.” India Herald, February 13, 2019. https://india-herald.com/pratham-houston-readathon-p6837-65.htm.

Natesan, Durga. “Expressions of Hope – Rohini Bulusu.” Asha for Education - Silicon Valley, February 10, 2018. https://sv.ashanet.org/blog/2018/02/expressions-of-hope/.

“Pratham USA Homepage.” Pratham USA. Accessed March 12, 2022. https://prathamusa.org/.

Pratham USA. “Pratham Houston Launches Summer Readathon for Children.” Leading South Asian newsweekly based in Houston, Texas., July 5, 2019. https://www.indoamerican-news.com/pratham-houston-launches-summer-readathon-for-children/.

Pratham USA. “Triveni Dance Ensemble Hosts Benefit Performance for Pratham.” Pratham USA, May 24, 2017. https://prathamusa.org/triveni-dance-ensemble-hosts-benefit-performance-for-pratham/.

Swamy, V Kumara. “10 Ngos Rejuvenating Education in India.” GiveIndia's Blog, November 18, 2021. https://www.giveindia.org/blog/top-10-education-ngos-rejuvenating-education-in-india/.

“Vibha Atlanta.” Vibha, 2018. https://campaigns.vibha.org/campaigns/atlanta-cricket-2018.

Vibha Atlanta. “FutureTech Vibha Champions Cricket Cup.” Vibha Atlanta, 2019. https://campaigns.vibha.org/campaigns/atlanta-cricket-2018.

“Vibha Homepage.” Vibha, December 27, 2021. https://vibha.org/.

Vibha Youth Chapter Bay Area. “Vibha Youth Hackathon.” Facebook, July 24, 2021. https://m.facebook.com/events/d41d8cd9/vibha-youth-hackathon/538910683779964/.

Vibha Inc. “Vibha Annual Report 2019.” Accessed March 13, 2022. https://vibha.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Annual_Report_2019.pdf.

Wells, Rob, and Anjna Raheja. “UK Asian Communities: A Profitable Market for Nonprofits?” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 2, no. 3 (1997): 233–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.6090020305.